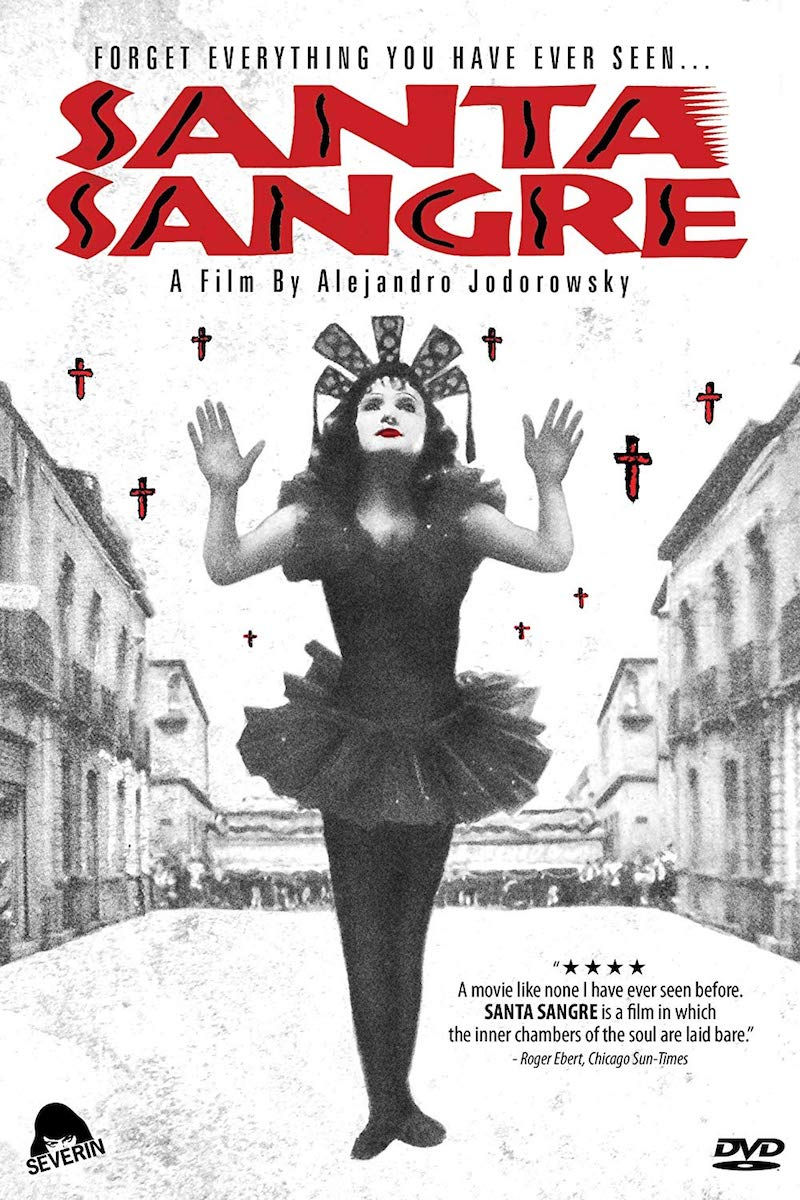

Translove Airwaves is thrilled to welcome the fantastic writer, Alex Deley, as a guest contributor to TLA. To coincide with the premiere of my psychedelic film series at Lost Origins Gallery in Mt. Pleasant, DC, I asked Alex to write a review for the first film in the series, Alejandro Jodorowsky's 1989 masterpiece, Santa Sangre.

Santa Sangre and the Return of Alejandro Jodorowsky by Alex Deley

The one predictable thing about the work of the Chilean psychedelic filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky is that one should expect the unexpected. This adage holds true of Jodorowsky’s 1989 comeback film, Santa Sangre. The film was made and set in Mexico and finds Jodorowsky rediscovering his powers as a filmmaker following nearly a decade in the wilderness. While Jodorowsky is best known for his twin early ‘70s acid-inflected midnight movie classics, El Topo and Holy Mountain, the Santa Sangre project had followed twin failures by Jodorowsky.

He had attempted both a doomed but outrageously ambitious adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune (that unmade film remains one of the great “What ifs?” in cinema history and is the feature of the excellent 2013 documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune) and had regrouped from that experience with a critically savaged children’s fable, Tusk in 1980. Following Tusk’s poor reception, Jodorowsky had walked away from the cinema and begun a promising career as a European comic book author, putting to use, in another medium, many of the concepts he had worked on for his abandoned Dune project. As such, his return to filmmaking was both unexpected and insured that Jodorowsky came back with a point to prove.

Produced by legendary Italian Giallo filmmaker Dario Argento’s older brother Claudio Argento, Santa Sangre is a surrealistic slasher film that plays like a mixture of Hitchcock’s Psycho, the silent horror classic, Hands of Orloc and Jodorowsky’s own earlier work. The film provides nods to many other classic horror films, including The Invisible Man from which it weaves a disturbing mirrored scene. The plot of the film centers upon the trauma of a young boy, Fenix (played at different ages by Jodorowsky’s sons, Axel and Adan), who grows up in a dysfunctional family of circus performers and the collective, madness-inducing trauma that they experience in the aftermath of said trauma. Leo Tolstoy famously wrote that, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” and this movie takes this conceit to its logical extreme.

Fenix’s father (played by Guy Stockwell) is drunken and libidinous master of ceremonies who doubles as a knife thrower and master hypnotist. He is actively having an affair with a heavily tattooed sex pot of an assistant, an issue that proves to be intolerable to Fenix’s mother (played with a Machiavellian perfection by Blanca Guerra), a circus acrobat by night and cult leader by day. Indeed, Fenix’s mother begins the movie reeling thanks to the destruction of her cult and church, the titular Church of the Santa Sangre, and her discovery of the affair only deepens her sense of aggrieved trauma. The discovery of her husband’s adultery sends her into a bloodthirsty rage that results in both the eventual death of her husband but not before the horrific severing of both her arms at her husband’s hands. Fenix is driven mad by witnessing both the destruction of his family and the loss of his only true friend in the circus, a deaf and mute girl who works as a tightrope walker who is kidnapped by the tattooed object of his father’s lust in the immediate aftermath of the Fenix’s mother’s rampage.

A now older Fenix is institutionalized and seems unreachable until a trip to the cinema (and a chance run-in with a cocaine-peddling pimp) sees Fenix escape the asylum staff and sets him on a path wherein he is shortly reunited with both his disfigured mother and eventually the tightrope walker from his youth.

However, all is not righted and he falls under his mother’s sway, becoming her arms in a circus act. Fenix's mother also takes up a sideline in manipulating Fenix into murdering other women at her behest as part of a greater cosmic revenge against the tattooed woman who stole her husband.

Jodorowsky does a wonderful job of subverting existing slasher tropes, with the film’s closest cousin perhaps being Michael Powell’s (career-ending) slightly psychedelic early slasher, Peeping Tom. The film carefully combines the dusty Mexican landscape with bright colors, befitting its circus background, strange sights and sounds and precise production design. In typical fashion, Jodorowsky repeatedly drifts the film into nightmarish dream sequences where Fenix is confronted by the memories of the women he kills at his mother’s behest, further cementing his madness. Jodorowsky knows how to maximize the otherworldly feel of these segments and makes sure that they land with a punch, crafting haunting imagery that lingers in the mind long after the credits roll. The film also manages to weave in moving elements of innocence and sweetness. While Fenix is never truly redeemed or freed from his fate, his relationship with the mute tightrope walker (and his eventual reunion with her) provides something of the emotional core of the movie. Jodorowsky’s time away from filmmaking seems to have given him opportunity to sharpen his emotional and empathetic capabilities. Those familiar with the cinematic acid trips of his earlier work will be rewarded by the deeper characterization found here without any compromise in the sheer craziness of the content.

Another key weapon in Jodorowsky’s arsenal is English composer Simon Boswell’s mesmeric score to the film. The music is deployed throughout, sometimes in ways that augment and provides greater emotional depth to a given scene, sometimes in ways that undercut the text and provides an otherworldly subtext. The variety of different styles that Boswell works in throughout is breathtaking, ranging from traditional mariachi, to gorgeous minor key quasi-flamenco guitar pieces, to icy and sinister synthesizers. Boswell is well known for his ability to combine technology with traditional film orchestration and he proves to be an ideal collaborator for Jodorowsky, with his score work almost becoming like another character in the film. This score, replete with its quasi-spiritual overtones in places, prefigures work that Boswell would later do for the Vatican: an interesting shift from the cult of “holy Blood” to the genuinely liturgical. Boswell’s work is also augmented by cunning deployment of traditional Latin pop numbers, including recurrent usage of “Cabello Negro” by Cuban Mambo pioneer, Pérez Prado, and a stunning read on the Latin standard “Besame Mucho”. All in all, Santa Sangre proves itself to be more than just a horror genre exercise or a purely psychedelic experience. It emerges as a deeply rewarding meditation on dysfunctional family dynamics and how family trauma can manifest as madness later in life. This is a more mature version of Jodorowsky, with his core personal obsessions still in tact but married to a deeper psychological subtext. Where Jodorowsky previously preferred to use the tarot, the Jungian collective unconscious and mythology in order to excavate deeper meaning from his work, here the meaning is more directly textual. Santa Sangre then, represents the first of a series of highly personal films from an uncompromising filmmaker that would continue through to his most recent works The Dance of Reality (2013) and Endless Poetry (2016). This is a film that will continuously wrong-foot you but which lingers on well after the madness has subsided and the world has gone calm again. It is not to be missed.

Komentáre